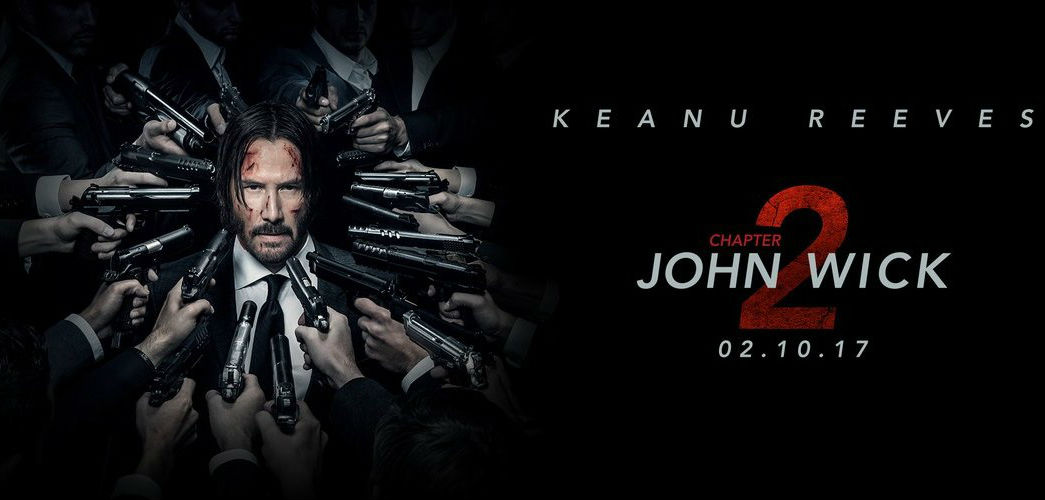

What is it with sequel titles this year? John Wick: Chapter 2, Guardians of the Galaxy: Vol 2… it’s like there are just too many sequels to name. That being said 2017 seems to be the year of good sequels. Split (2017) which is positioned in the same universe as M. Night Shyamalan’s Unbreakable (2000) got great reviews, The Lego Batman Movie which is a follow up to 2014’s surprise success The Lego Movie seems to be getting rave reviews, and of course, there’s John Wick: Chapter 2.

When analysing a film, one of the things I try to look out for is the scene that is included in excess of what is absolutely necessary for narrative development and progress. And the opening shot of the John Wick sequel provided just such a filmic moment. A black and white clip of a scooter stunt projected on the side of a building apropos of nothing preceding a pan downwards to a motorcycle skidding on a road. The two sequences obviously mirrored each other and spelled out the film’s thesis and lineage in one fell swoop.

The black and white clip recalls the era of early films from the 1900s before even Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, where vaudeville danger acts were the source of most of the silver screen’s inspiration. What John Wick: Chapter 2 tries to remind the viewer then is that these spectacle-intensive single reel films are the precursor to the modern day action film. The fact that the film opens with a car chase scene further supports this claim because, you know that saying, “cut to the chase”? That came from roughly the same film era. People just wanted to cut to the chase, the meat of the film, the part where all the action was – the most intense scene, and the most exciting one that would keep the audiences hooked and on the edge of their seats.

Thus, the sequel serves to remind us that when watching a John Wick film, one is well and truly a spectator spectating a series of spectacles. The structure of both films are fairly similar and could almost be called episodic with simple motivations moving characters from one action-packed sequence to the next. This is not unlike how George Melies used to make his trick films and early feature length films:

As for the scenario, the ‘fable,’ of the ‘tale,’ I only consider it at the end. I can state that the scenario constructed in this manner has no importance, since I use it merely as a pretext for the ‘stage effects,’ the ‘tricks,’ for a nicely arranged tableau.

– George Melies qtd. in Tom Gunning’s “Cinema of Attraction”

When seen in this light, it would explain a little bit why the momentum of the opening act in the John Wick sequel seemed to stutter a little when they tried to insert a recap of the first film.

That being said, the opening act was surely a homage to the action film genre and the franchise’s first installment that was the sleeper hit of 2014 that has since been hailed as one of the best action films in recent years. This is clearly felt from the range of shots and filming techniques presented in the opening sequence to remind the viewer of how far film has progressed in its strategies and effects used to capture and present spectacle.

In the early days of film, stunts and performers’ skill could only be captured through the use of long shots and long takes. But proceeding from the long shot in the black and white projection, we see that the camera is moved closer and closer to the action where audiences are no longer positioned on the outside as spectators but on the inside as participants.For instance, the placement of the camera alongside John Wick’s Dodge Charger as it races along as part of the car chase sequence allows audiences to participate in the thrill and the exhilaration of moving alongside a speeding car.

The long shots and long takes are still present, but are reserved for complicated auto stunts and when John Wick (Keanu Reeves) kicks ass. The mobile camera is used to accentuate action sequences and follow along the trajectory of a punch, like when Wick delivers a finishing blow, to capture the impact of the hit. And if I’m not wrong, there was a scene where a bike flips towards the camera that looked like it was a CGI shot.

And just like that, the opening sequence becomes a catalogue of action film camera techniques. But because of the ascension of the narrative film and the banishment of the cinema of attractions that was forced to go to ground and coexist as an embedded component of certain genres of the narrative film (eg. musical, horror, fantasy, science fiction, action), the opening spectacle also had to give way to more narrative impulses. In a neat segue from spectacle to narrative, character psychology is reinjected once again into the film using the car and the contents of its glove compartment.

Thus Wick’s Dodge Charger becomes both the vehicle for action and narrative drive. And by the end of the opening act, you feel like you’ve been issued an invitation to come along for one hell of a ride.

Gunning, Tom. “Cinema of Attractions.” Early Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative. Eds. Thomas Elsaesser and Adam Barker. London: British Film Institute, 1990. 56-62.